- Nov 25, 2025

- 4 min read

When Did Design Stop Being Slow?

A reflection on speed, depth, and the craft we’re losing.

There was a time when design unfolded like a conversation. Not the rapid, compressed exchanges we have now through screens and Slack channels, but the long, meandering kind that let ideas breathe. A time when designers thought through their hands — shaping clay, sketching on tracing paper, redrawing the same form until thought, material, and intention began to align. Back then, slowness wasn’t inefficiency; it was discipline. Time was a tool of refinement. Reflection was part of the process, not a luxury.

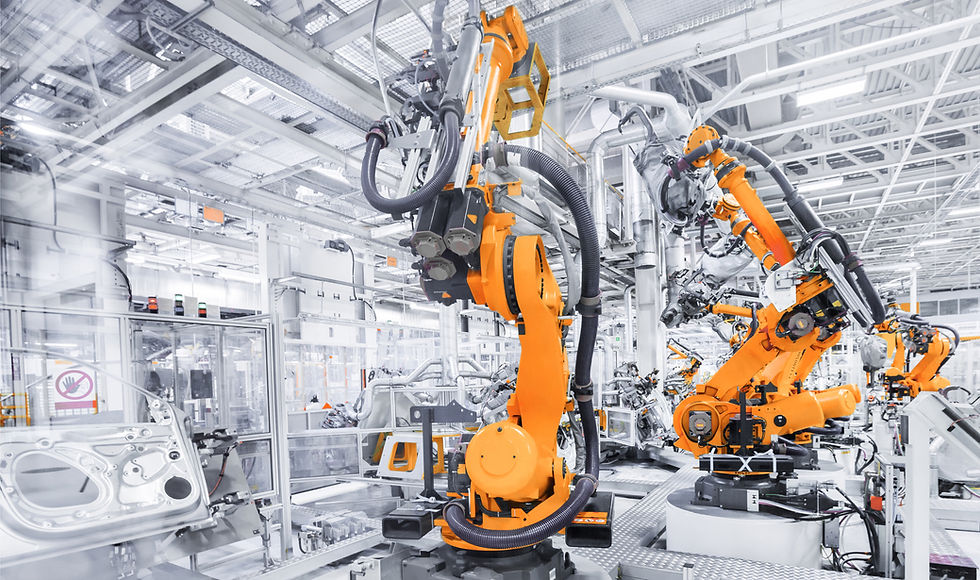

Then the world accelerated. Computers replaced drawing boards, CAD replaced clay, and AI now generates what used to take weeks of iteration. What began as tools for progress gradually became symbols of speed. We stopped asking whether acceleration served creativity — we simply assumed it did. Every innovation that promised to save time also quietly rewrote how designers think. Software shortened feedback loops. Clients expected deliverables

faster. Algorithms began predicting what we might draw before we’d even decided what we wanted. Speed made us productive but also restless. When every idea can be visualised instantly, iteration loses its meaning. There’s no friction, no resistance, no discovery — just production. The price of acceleration is subtle but corrosive: we start confusing movement with progress. I see it often in projects where visual polish masks conceptual thinness. The prototype looks stunning, but the story beneath it is fragile. We’re producing surfaces faster than we can fill them with substance. Design has always been a conversation between intuition and intellect. When everything becomes a sprint, intuition gets left behind.

Slowness, in design, isn’t about inefficiency; it’s about depth — the willingness to stay inside the problem long enough to understand it from the inside out. The best ideas don’t arrive fully formed; they emerge gradually, like film developing in the darkroom. That process can’t be rushed. It depends on silence, iteration, and doubt.

At WOWME, I’ve seen the power of deliberate pace: the extra day spent refining a curve, the hour of dialogue that reveals a user insight, the patient study of a material’s behaviour under light. These aren’t delays; they’re investments in meaning. In an age obsessed with deliverables, the ability to slow down becomes a competitive advantage. Because speed can imitate skill — but never wisdom. Time leaves fingerprints on design. You can feel it in objects that were crafted, not merely produced.

When I hold a time, it leaves fingerprints on the design. You can feel it in objects that were crafted, not merely produced. In every enduring product from the mid-century masters — the balance of form and restraint, the quiet honesty of function — there’s a rhythm of thought embedded within the material. Every joint, proportion, and radius reveals a negotiation between vision and limitation. Those constraints forced ingenuity. Now we have an abundance of tools, data, materials — but a scarcity of patience. We can simulate perfection in hours, but what we gain in efficiency, we lose in intimacy.

There’s a quiet intelligence in slowness. It teaches respect for materials, empathy for users, and humility before complexity. The time we spend understanding a problem often determines whether the solution feels inevitable or forced. Slowness gives the product a soul. Craft isn’t nostalgia; it’s consciousness. To craft is to pay attention — to know why something looks, feels, or functions the way it does. It’s the antidote to automation, not because it rejects technology, but because it humanises it.

Digital tools can enhance craft, but only if we use them as extensions of thought rather than replacements for it. CAD can visualise precision; AI can generate options. But neither can care. At WOWME, we see technology as a collaborator, not a substitute. The machine can accelerate production, but only the designer can give form to purpose. Craft today means choosing when to move fast and when to linger, keeping the tactile and emotional alive inside the digital.

When I teach design, I remind students that software doesn’t design — they do. Tools are mirrors, not muses. If you move too fast, you start to believe the screen knows more than your hand.

We’re standing at a crossroads between craftsmanship and computation, patience and performance. Perhaps our challenge now is not to reject speed but to redefine it — to recognise that there are different kinds of speed: the speed that gets things done and the speed that gets things right. The first is measurable; the second is meaningful.

The designer of tomorrow will master both — the agility to move fast when necessary and the wisdom to slow down when it matters. Maybe, in the end, slowing down is not about doing less but doing with intention. It’s about designing at the pace of understanding.

Because the real question isn’t when did design stop being slow, but when will we allow it to be slow again? When we remember that quality isn’t about moving faster, it’s about taking our time to notice.

If your team is feeling the pressure to move fast but fears losing meaning in the process, let’s talk. At WOWME, we help founders and innovators design at the right speed — where craft meets clarity, and progress still feels human.

Comments